I met Dominika Wojtkowska in the basement of Konrad Café, where her office is discreetly set behind a glass wall—a compact, functional studio embedded within one of Luxembourg’s best-known cafés. She designed this part of the space herself, during a renovation project that gradually became a long-term collaboration with the owner. It’s emblematic of how she works: from inside a place, quietly shaping it with care and attention to detail, often without public recognition.

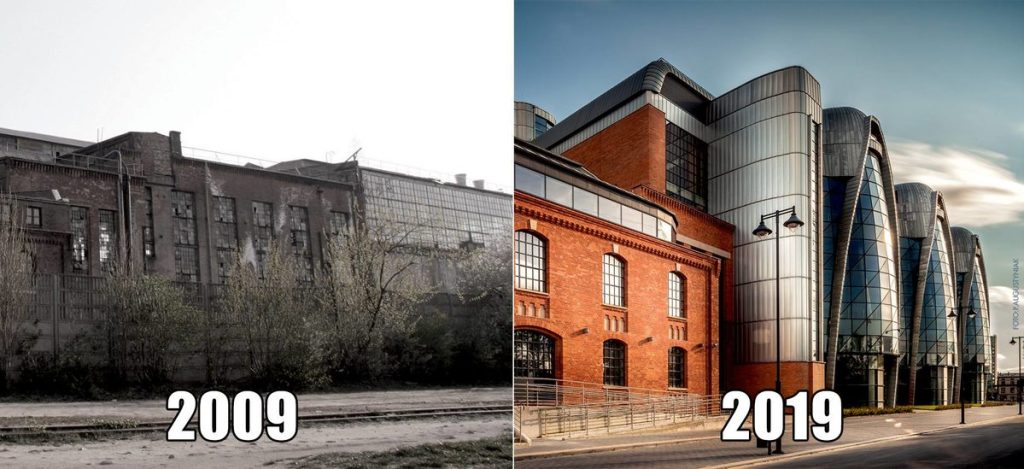

Originally from Poland, Dominika is an interior architect who has been based in Luxembourg since 2014. Her work, however, stretches far beyond the Grand Duchy. Before relocating, she spent nine years in Poland leading major architecture projects, including the National Film Center in Łódź—a large-scale redevelopment of an industrial site into a creative and cultural hub. That experience, which included collaboration with director David Lynch, shaped her perspective on how architecture can respond to human needs—not just structurally, but emotionally and sensorially through the five senses. “It is so important for me that I understand needs from the client, and I’m following the five senses to develop it in a way that will be best for their spaces.”

Dominika’s career reflects a broad and cross-disciplinary education, with studies in Poland, the US (Ohio), and Lithuania. From digital technologies like 3D scanning and printing to more analogue disciplines like fashion and photography, she’s taken a wide-angle approach to design, yet always with a focus on how people live and interact with space.

In Luxembourg, her portfolio includes work on well-known hospitality venues like Konrad, Go Ten, and Mirador in Clausen. She often works with historic or protected buildings, which brings its own set of constraints. At Go Ten, she removed layers of paper to reveal original brick walls and introduced better lighting and acoustics. “It was a slightly younger building, so less complex,” she noted, and included accessible features like a lift to the toilets.

Accessibility is a recurring challenge in Luxembourg’s older buildings. “It’s very tricky,” she said, referring to efforts to install ramps or lifts in the Old Town, where architectural protections are strict. She is currently working on making the upper level of Konrad easier to navigate for wheelchair users.

“Sustainability for me means working with what’s already there,” she tells me, pointing to the original staircases and vintage furniture she kept during the Konrad renovation. In her projects, modern technology is used with restraint. She favours durable materials, and where smart features are introduced, they serve to support rather than overwhelm the space. A solar panel that looks like slate, a sensor-activated ventilation system, or discreet lighting that adapts to time of day—all are integrated with care.

This kind of design thinking—conscious of sensory experience and human need—is increasingly relevant. Dominika explores how sound, touch, light, and temperature affect wellbeing. She’s interested in how design can support neurodivergent users, or improve comfort in everyday domestic settings. Her recent research includes work on lighting for learning environments and sensory zoning in homes.

She also brings this thinking into her own spaces. An early renovation project in Luxembourg was a house in Bonnevoie, designed to balance aesthetics and everyday function. She included a feature that allows the homeowner to see their car from inside—a detail that speaks to how people value their belongings and want them reflected in their environment. She is currently renovating a second property.

Alongside large-scale projects, Dominika continues to explore smaller tactile works, such as a series of wall-mounted rugs shaped like insects. Each piece is handmade, designed to engage the sense of touch, and no two are alike. “They’re not decorative,” she explains, “they’re meant to be used and felt.”

Her practice, LiveTouch, takes its name from this philosophy. Whether she’s restoring original features in a protected building or experimenting with waterproof wallpapers to update bathrooms without removing tiles, the focus remains the same: how spaces feel, how they function, and how they age with their users.

In a city where design is often overshadowed by finance, Dominika’s work reminds us that the places we eat, meet, and live in are quietly shaped by decisions most of us never see. But we do experience them—through light, sound, texture, and mood.

Her work may be quiet, but it’s impossible to ignore.

Neuroarchitecture of Interiors: Dominika’s Quick Guide for Intentional Design

- Design for all five senses

Don’t just focus on visuals — include light, sound, touch, scent, and spatial rhythm.

- Support natural movement

Balancing furniture, flexible zones, and posture freedom help regulate focus and energy.

- Balance sensory aesthetics

Neutral base + curated accents = stimulation without overwhelm.

- Create emotional safety through space

Natural materials, warm lighting, and soft textures provide comfort to the nervous system.

- Design for feelings, not just style

Ask: How do you want to feel in this space?

Adapt the environment to the user’s sensory and neurological needs with Livetouch.design

Read more articles:

Vanillana’s Pastries Blend Art, Flavour, Passion

Smart Stays In The Grand-Duchy: Flexible Housing Solutions In Luxembourg