From sci-fi’s forgotten founder to zero-emissions in Antarctica, Luxembourg keeps punching above its weight — with five global firsts that prove small nations can still think big.

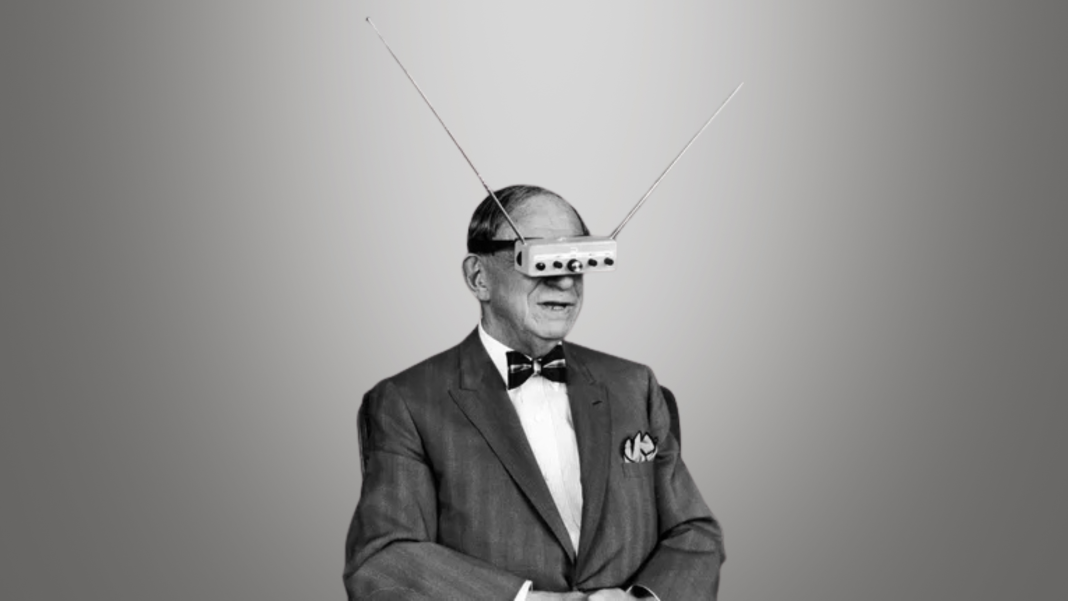

The first science fiction mastermind

Science fiction didn’t start in Hollywood. Or Silicon Valley. If you’ve ever read about far-off worlds, or debated space lasers online, thank Hugo Gernsback — a Luxembourger who imagined it.

Gernsback was born in Luxembourg City in 1884. He studied engineering and industrial arts, then left for America at 20 and started inventing things. Among his early inventions was a wireless telegraph — a precursor to the walkie-talkie.

Gernsback was an entrepreneur, importing specialised electronic equipment from Europe and helping to supply many Americans who wanted to dabble in a new technology and make their own radios and transmitters. In 1908 he founded Modern Electrics, the first magazine about both electronics and radio, then several others focused on science and invention.

But Gernsback’s real legacy was imagination.

He wrote, edited, published, and promoted stories about future worlds, space travel, and weird machines. While the prose was often rudimentary, it sparked imagination and seeded a new genre.

By 1926, Gernsback was publishing Amazing Stories, the first magazine dedicated to sci-fi—though he called it “scientifiction” at first. Though Jules Verne imagined moonshots six decades earlier, Gernsback built a new genre. His publishing efforts spawned more than 50 newspapers, illustrated magazines, humorous journals, weeklies and monthlies devoted to technology and popular science.

The Hugo Awards, sci-fi’s top prize, were named after him in 1953.

What would Gernsback say if he saw the country just moving into industrial production when he left was now designing shoebox-sized crawlers for the lunar surface and robot arms to fix satellites soaring through space? Science fiction.

Richest country – with an eye on the lowest earners

Luxembourg sits at the top of the global rich list — at least by the salient measure of gross domestic product per capita when adjusted for real purchasing power. The World Bank said that figure was an impressive $150,772 last year – more than double Germany’s. And Germany isn’t exactly struggling.

Luxembourg’s size certainly helps. With fewer than 700,000 residents and a thriving finance sector, there’s plenty of money to go around. Wealthy bankers, investment firms, and a strategic location in Europe all play a role. So do the 200,000 or so workers who commute in daily from France, Germany, and Belgium — earning money in Luxembourg but not adding to its population stats.

Luxembourg also has been keen to distribute that money. The minimum wage is the highest in the OECD, and probably the world. As of 2025, even unskilled workers are entitled to about €2,700 a month. Skilled workers make more than €3,200.

In Luxembourg, even average wages reflect extraordinary prosperity.

Stuck in traffic

Maybe because Luxembourg is as rich as it is tiny, it also has the highest per capita car ownership in Europe. Nearly every household owns a car and some own three. Petrol prices remain among the EU’s lowest.

In 2020, the government tried something bold: in a global first, it made all public transportation free. Buses, trains, trams—zero fares for everyone, visitors included. There are even late-night buses and door-to-door minivans.

The goal: reduce car use and ease congestion.

But traffic barely budged. It turns out that people don’t value free rides much if trains are late or buses don’t go where you need.

The country plans to expand its tram lines and upgrade railroads. But will that be as easy as hopping in your car?

Transport is free — but the roads still cost time, especially at 8 am on a Monday.

Innovating for financial markets

Before global financial hubs dominated headlines, the Luxembourg Stock Exchange quietly made history. It was the first in the world to take a step that helped create modern international capital markets.

Soon after the US changed its tax laws in 1963 to make investing abroad less attractive, the Luxembourg market hosted Italian motorway builder Autostrade as it sold bonds worth $15 million. Not Italy’s currency of that time, the lira.

So-called Eurobonds were a new idea – a debt instrument issued in a different currency than the one used in the home of the borrowing company or the securities market.

At a time when Europe’s capital markets were mostly closed-off and everyone stuck to their own lanes, Luxembourg offered a new route to the future.

Since then, Luxembourg became the first exchange in 2007 to list a “green bond”- a security used to raise money for environmental projects. By 2016, it launched the Luxembourg Green Exchange, a platform just for green, social and sustainable securities. Now the exchange lists over 2,200 of them.

Not bad for a country often associated more with castles than capital markets.

Luxembourg builders took on polar extremes

It’s not every day a Luxembourg construction company finds itself building in Antarctica. But that’s what Prefalux did — shaping an Antarctic outpost on a ridge 200 km from the coast which runs entirely on wind and sun and shrugs off -50°C temperatures.

The Princess Elisabeth Antarctica station, built at nearly 1,400 metres altitude, is the world’s first zero-emissions polar research base. No oil or chimneys. Just solar panels, wind turbines and a very smart grid.

Luxembourg construction firm Prefalux made the wooden frame, outer walls and roof. Components were built in Luxembourg, pre-assembled in Brussels, then shipped south to the bottom of the Earth. Assembly had to be done fast: builders had about 10 weeks before the weather turned from awful to impossible.

The result is a sleek, self-powered research hub that houses up to 50 scientists in the middle of nowhere. Compact, efficient, and built to endure winds of up to 250 km/h, for their efforts, Prefalux won the Chamber of Trade’s trade innovation prize in 2008. Having conquered the South Pole, space might just be next.

Read more articles:

Luxembourg Bets Big On Space Defence